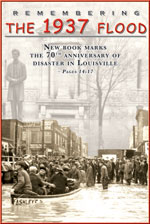

Remembering the 1937 Flood

New

book marks 70th anniversary

of Louisville’s experience

Author

Bell captures the effect on the city

and its people; will sign book in La Grange, Ky.

By

Helen E. McKinney

Contributing Writer

LOUISVILLE, KY. (March 2007) – Dennis Miller

vividly remembers being awakened at 2 a.m. or 3 a.m. by the Louisville

Fire Department to evacuate his Ormsby Avenue home when he was 7 years

old.

|

|

March

2007 |

Along with his parents and six brothers and sisters, the

family was bustled outside in the cold darkness of a winter night while

still in their nightclothes to board a waiting flatbed wagon that would

take them to safety.

Water covered the floor of his home and was “almost over the house

by the next day,” he said. Miller was referring to the flood of

1937, a natural disaster that displaced many families and forced some

to become homeless refugees for quite a long time.

Miller and his family stayed with his grandmother at Preston and Lee

streets in Louisville, “and we almost had to leave there”

because of the rising water. Unable to walk down the city streets, his

father and two brothers took a boat back to their home to get clothes.

The thing he recalls most is “my parents saying how devastating

the flood was for Louisville.” They also spoke of American Red

Cross efforts and food aid that was sent out to families in need.

The family had to wait a long time before they could move back home.

When they did, it was only after the plaster had been torn off the walls

and repaired and the house rewired.

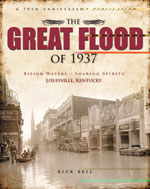

It is memories such as these that Louisville author Rick Bell has recorded

in a recently released book, “The Great Flood of 1937: Rising Waters,

Soaring Spirits.” Bell chronicles the emotions, facts and historical

significance of the event in the lives of many Kentuckians through photos,

historic maps, log books and diaries.

|

“The

Great Flood of 1937”

Like San Francisco’s earthquake and Baltimore’s

Seventy years ago, in January 1937, the Ohio River flooded in biblical proportions. Like New Orleans after Katrina, two-thirds of the city of Louisville, Ky., was under water. But the citizens of Louisville, under the inspired leadership of Mayor Neville Miller, fought

This is the complete story of those heroic days. Through historic photographs, maps, log books, diaries and personal recollections, author Rick Bell re-creates, in thrilling detail, the magnitude of the devastation and the totality of the city’s eventual triumph. Source: Book publisher’s note |

The Ohio River flooded in wintertime in late January and

early February 1937. Families found themselves cold, homeless and hungry

during a period when the country was in the middle of the Great Depression

following the Dust Bowl.

The river was above flood stage for 23 days, with flooding from Pittsburgh

down to Cairo, Ill. More than 1 million people were homeless along this

route, with 385 dead. Property losses topped $500 million.

“It was the greatest natural disaster up until that time,”

Bell said.

More than 19 inches of rain fell during January, leaving more than 60

percent of Louisville under water and without power. Businesses were

devastated. Other areas, such as the 118-acre Rose Island amusement

park, was lost and never rebuilt.

“I’ve been interested in the flood all my life,” said

Bell, 60. He grew up in the Portland area of Louisville and remembers

his family relating stories of the flood. Growing up in Louisville in

the 1950s, “you heard people talk about it.”

Bell’s parents lived above a grocery store, and for this reason

faired better than some. His brother was six months old at the time,

and the family had to live in the attic amidst valuable antique furniture

his mother had stored. It was this same furniture that was burned for

his brother to have dry diapers.

Bell’s mother died 1 1/2 years ago, and she is partly the reason

he wrote this book.

“People really do want to share their story and experiences,”

he said.

Portrait artist and former Louisville resident Geraldine McCollum was

4 years old in 1937. Like Miller, she recalls her family being awakened

in the middle of a dark night in Louisville’s Portland neighborhood

and taken to the fire station in a mail truck.

“It was a very dark night, no lights in the neighborhood,”

said McCollum, who now resides 50 miles upriver in Madison, Ind.

|

|

Photo

by Caufield and Shook Collection “Lincoln

Standing on Water,” one of |

She’ll never forget “the fear” and hearing

the cries of people all around to “send a boat” in the black

darkness. You’d really have to experience it.”

After his family was safe, her preacher father spent the remainder of

the night assisting rescue efforts. During this devastating time, there

was one small spark of humor to the situation.

In the confusion of darkness and sudden fear, McCollum’s mother

accidentally tied the strings of her 7-year-old brother’s knee

boots together. “This rather hampered his movement in that excited

darkness!”

In his past position as assistant to the director of the Filson Club,

Bell gave a presentation for the 50th anniversary ceremony of the flood.

This information formed the core of his book. “There were lots

of remembrances for the 50th anniversary,” he said.

Some of the photos in the book have never before been published. The

University of Louisville staff members worked with Bell, giving him

access to the thousands of archived pictures in their archives.

James Manasco served as photo editor for the book and works in Special

Collections at the U of L’s Ekstrom Library, where the photos are

stored. “We should preserve our history,” said Manasco.

|

|

Photo

by R.G. Potter Collection Louisville’s

flood brought out the |

The Ekstrom Library has more than 40 collections of archived

flood photos, some of earlier flood periods (1884) and even the mayor’s

scrapbook. There are almost 2 million images stored at U of L, Manasco

said.

Individuals have donated much of this material, but there were several

local major photography companies that had saved negatives and donated

their collections as well, said Manasco.

The significance of these photos lies in the fact that many of them

are the only remaining record of some of the buildings that once stood

in downtown Louisville.

“It’s important to know where our culture has been,”

he said. These images show what America, not just Louisville, would

have looked like at the time.

The flood “touched everybody in this community,” said Bell.

“It reshaped the community. There are a lot of people around who

experienced it. It’s what made us who we are today.”

Ruth Klingenfus, 85, lived in Pewee Valley, Ky., at the time of the

flood. She remembers attending school in nearby Anchorage. The school

had to close for a time because of the flood.

|

1937

Flood Facts:

• Four

of the greatest floods of the Ohio River Valley occurred in 1884,

1913, 1937 and 1997. |

“It was quite a hard time,” she said. “Many

people lost a lot of things.”

Klingenfus’ husband, Carl, had an aunt in the St. Matthews area

with whom he went to stay. But many people had to leave Louisville and

find temporary shelter in surrounding counties, such as Oldham and Shelby.

“People were brought out to more secure places,” she said.

One of these shelters was the vacant Confederate Home in Pewee Valley.

During this time, Sis Marker, 88, went to work there for the Red Cross.

“Two hundred refugees came to the Confederate Home,” she said.

Marker was attending Spencerian College at the time and remembers coming

home on the last day of school with Klingenfus’ sister, Anne Malone.

“We had to detour to get home.”

She had an aunt that lived on Preston Street come and stay with her

family. When relatives went back to her home to see what they could

salvage, she told them to get her dog at all costs. “She would

rather have been shot than to have lost that dog,” said Marker.

“We were proud to publish this book,” said Carol Butler of

Butler Books. “Not only did Rick Bell do a fantastic job recounting

the 1937 flood, it was a commemorative book. It’s important for

the community to capture their personal recollections.”

Butler said her company published this book because “it was a role

we wanted to play. These stories will live forever and capture a legacy.”

For the past 2 1/2 years, Bell has served as the executive director

of the U.S. Marine Hospital Foundation, where he is overseeing restoration

of the historic building. (See the RoundAbout article on the U.S. Marine

Hospital at our website under “Archived Articles” and click

on “December 2005 stories.”)

• Author Rick Bell will hold a book signing at

Karen’s Book Barn & Java Stop, 127 E. Main St., La Grange,

Ky., from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. March 17. Visitors can purchase the book

for $25. Call (502) 222-0918 for information. The book is also available

at Louisville-area bookstores or ordered directly from Butler Books

by calling (502) 897-9393 or by going online at: www.butlerbooks.com.

• To donate photos or other collections to the U of L Ekstrom Library,

contact James Manasco at (502) 852-8731 or Amy Purcell at (502) 852-1861.

• The Oldham County History Center is also interested in collecting

memoirs and photos of the flood to add to their collection. Contact

Executive Director Nancy Theiss at (502) 222-0826 or email her at: ochstryctr@aol.com.

• The Jefferson County (Ind.) Historical Society Museum Archives,

615 W. First St., Madison, Ind., also has a large collection of 1937

Flood photos in its collection. Contact archivist Ron Grimes at (812)

265-2335.